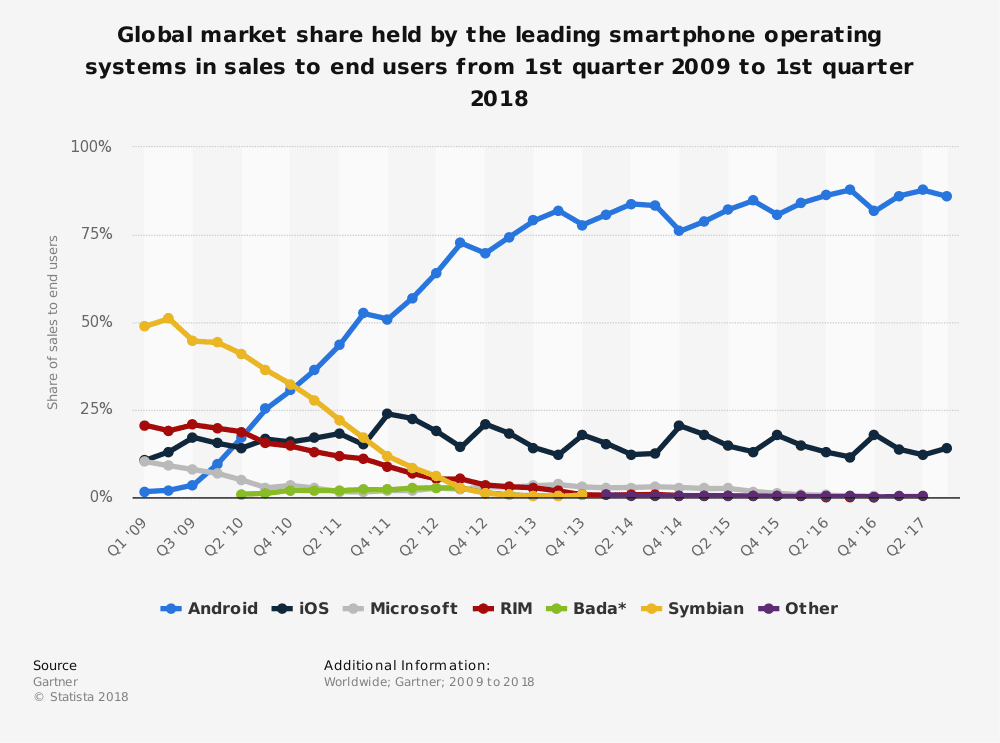

In 2009, the Android mobile operating system had less than three percent of market share. Symbian had over fifty percent of market share. By the end of 2017, Android’s market share had soared to close to ninety percent while that of Symbian had tumbled to effectively zero.

This dramatic exchange in market share provides valuable insights for business leaders concerned about disruptive digital technologies. What key insights can be derived from this cautionary tale that is the Android/ Symbian Greek tragedy?

1. Do Not Ignore Edge-case Scenarios

An edge case refers to any event that occurs at extreme (maximum or minimum) operating parameters. In a market context, edge-case scenarios are events that occur outside of anticipated market conditions. For instance, the rise of Android was occasioned by a rapid increase in microchip processing power (an edge case event), which effectively shrunk computers into handheld devices and sparked the smartphone revolution.

While Nokia was hard at work building a hardware business based on so-called dumbphones, Google instead saw an opportunity to become the Windows equivalent for this new class of computers. For business leaders, this insight proposes that some of the next biggest opportunities will be found in edge-case scenarios and not within normal market conditions.

2. Disruption Happens Hard and Fast

Symbian, a mobile operating system initially developed for PDAs and Nokia devices, lost its market dominance to Android seemingly overnight. Not accounting for the rapid rise of software as a fundamental building block of disruptive digital technologies, within eight years, Symbian went from a fifty percent market share to less than one percent.

Focused on engineering hardware, Nokia missed the transition to software ecosystems.

Android developer Google understood this ecosystem shift and focused its efforts on developing a robust and highly-compatible open source operating system to run the mobile devices of the future. Today, Android is not only a mobile OS, but powers homes, cars, and home appliances. The lesson to learn here is market leadership can quickly be diluted as it is often difficult to respond to disruption in real time. Instead, market leaders must build mechanisms to anticipate disruption before it occurs.

3. First-to-Market Beats Best-in-Market

In terms of time to market, Nokia and Google each had a relatively equal amount of time to bring their operating systems to market. Corness Business Professors Timo O. Vuori and Quy N. Huy researched this topic in their journal on “Distributed Attention and Shared Emotions in the Innovation Process: How Nokia Lost the Smartphone Battle.” They found that Nokia erroneously focused on getting the right corporate structures in place to launch a formidable assault. On the other hand, Google quickly assessed the situation and acquired and deployed a yet-immature Android OS to capitalize on an emerging trend.

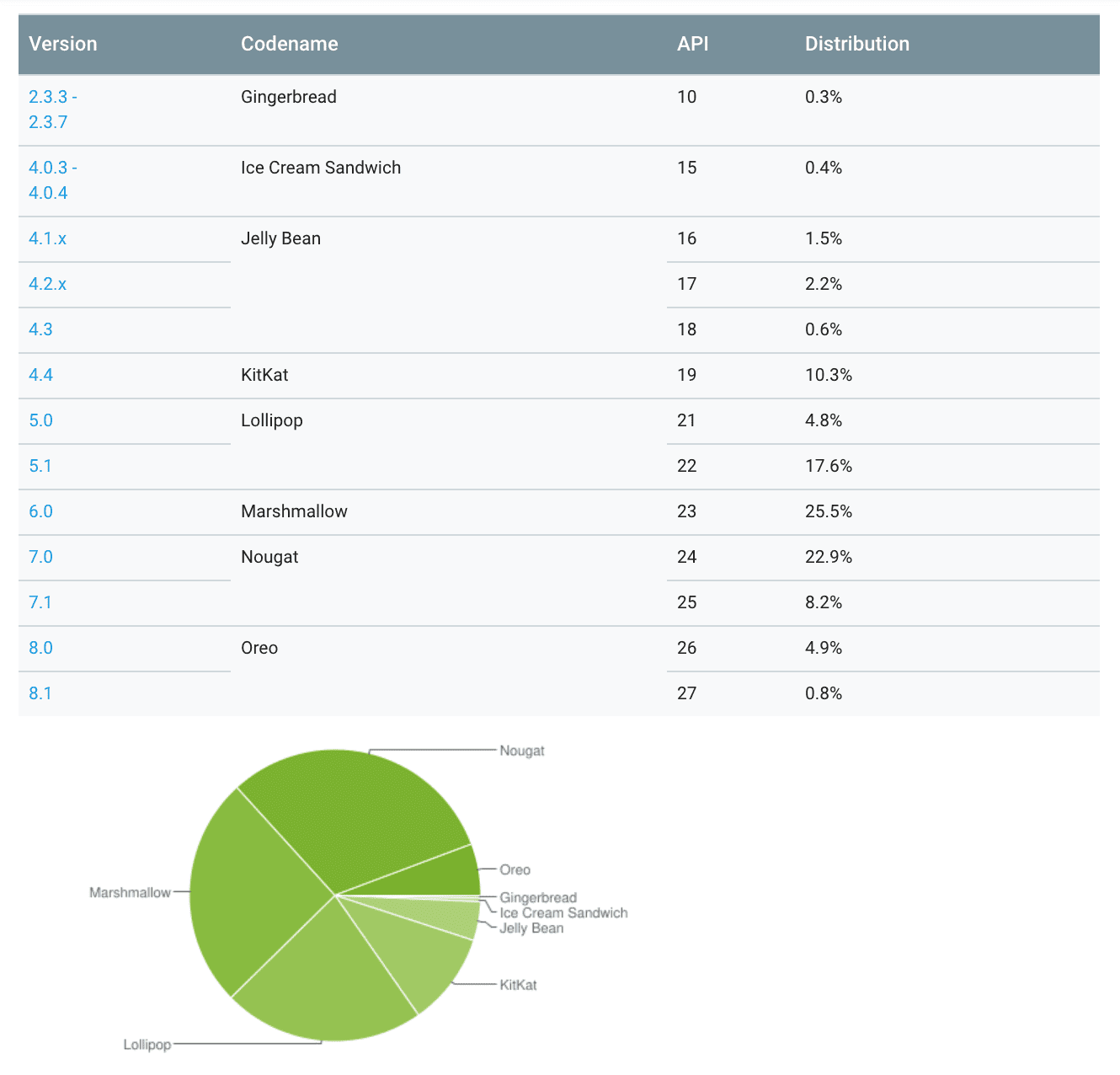

In fact, data from Google shows that Android is still grappling with a massively fragmented user base spread across its current thirteen Android versions. However, the cost of this fragmentation pales in light of the first-mover advantage Google achieved by moving fast. With first-mover advantage, it was easier for Android to achieve top-dog status, a fundamental insight leaders aspiring to drive disruptive change in their industries must internalize.

Conclusion

For business leaders to mirror this prototypical market dominance coup they must embrace the ideals at the core of this rise: find hidden opportunities in edge-case scenarios, look out for swift disruptive trends, and focus on being first-to-market, and not best-in-market.

The meteoric rise of Android is a poster child for disruption.